About 5 p.m. on a smoking-hot July day, Joyce Barnett called her husband, Bill, at work. She had no words; she could only shriek.

She’d just heard from friends of their 22-year-old daughter, Stacy. At Joyce’s request, they’d gone to Stacy’s apartment in Austin to check on her, but they found a crime scene instead.

Johnny Goosey, Stacy’s boyfriend, was sprawled in a pool of blood, dead.

The girls had no news of Stacy — police had shooed them away — but she wasn’t responding to phone calls, text messages or e-mail. That wasn’t like her; she was always plugged in.

Within the hour, the Barnetts were speeding toward Austin. They were in the car, on the highway, when Sgt. Hector Reveles from the homicide division of the Austin Police Department dialed Bill Barnett’s cell phone.

As Barnett remembers it, Reveles asked him to pull over.

“I don’t want to pull over,” said Barnett, terrified. “I don’t.”

Reveles said, “You have to pull over. I need to talk to you, and I’m worried about your safety.”

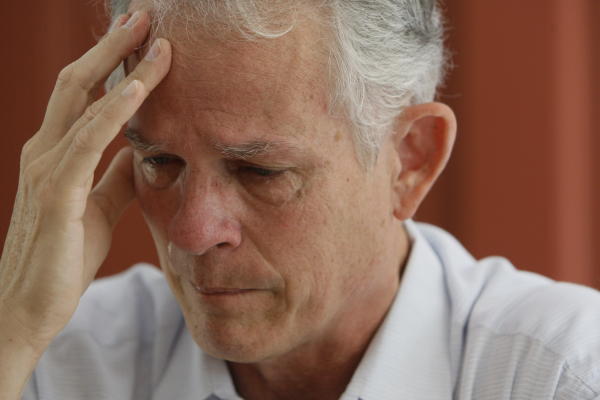

Barnett, who empties a box of tissue as he tells the story, remembers caring nothing about his own safety.

“There are two bodies in the apartment,” Reveles said. “One is Stacy.”

“You don’t know that,” said Barnett, grasping for any other explanation. “You don’t know my daughter.”

Almost six weeks after the slayings, the families of Stacy and Johnny are living out their worst nightmares. They’ve lost the young people they loved more than they loved themselves.

To compound the tragedy, Austin police are describing Johnny, 21, as a midlevel drug distributor who invited James Richard Thompson, now accused of capital murder, to the one-bedroom apartment to settle a drug debt.

The police stress that Stacy had no involvement in the illegal activities. Still, the news leaves both sets of parents — really, three sets of parents because Ricky Thompson is only 19 — reeling.

The Barnetts and the Gooseys, who buried their children side by side in Glenwood Cemetery, don’t accept the black-and-white police report. Still, as more information emerges, the families are haunted by very different questions. Here’s the one they have in common: What secrets did their children take to their graves?

A tragic loss

Stacy Barnett and Johnny Goosey grew up in the same wealthy city inside a city, West University Place. It’s a tidy, orderly community, one where furniture matches, bills get paid and accomplished parents raise accomplished children.

Since the July 21 murders, Goosey’s parents have not spoken in public. Joyce Barnett, Stacy’s mother, has remained silent as well.

Bill Barnett, however, wants to explain who Stacy was.

Even at birth, Barnett says, Stacy arrived without ceremony or roiling pain. At the hospital, Joyce told Bill she thought it was time, and before the doctor appeared, Stacy did.

She was a happy, serene infant, and in 22 years, Barnett can remember being frustrated with his younger daughter only twice — once when she was 3 and didn’t want to take a bath and again as a teenager when she experimented with cigarettes.

When friends or family members were having problems, Stacy made herself available. If they wanted to talk, she would talk. If they preferred silence, she was silent.

Throughout her school career, Stacy made excellent grades, tested well, took advanced courses and juggled homework with sports and social events.

She was in middle school when Bill Barnett fully realized that she influenced him as much or more than he influenced her. They were in Madrid, Spain, visiting Stacy’s older sister, Cathy, when Barnett tried without success to make a call from a phone booth.

Finally, Stacy put a calming hand on her frustrated dad.

“The phones don’t work the same way,” she said. “Would you like me to do it?”

Stacy stood about 5 feet tall, weighed about 100 pounds and wore her dark-brown hair long — sometimes. She was a regular donor to Locks of Love, a program to help children suffering from hair loss for an assortment of medical reasons, and she cut off her ponytail for those sick kids time and time again.

That meant friends were regularly asking, “Why did you do that?”

Barnett said she would shrug and smile. He never heard her brag about her gift or even explain it.

After Lamar High School, she went on to the University of Texas. When she was a sophomore studying in the prestigious architecture school, friends introduced her to Johnny.

Plans dashed

Dr. John Goosey is a respected eye surgeon. His wife, Claire, is a well-known volunteer. While they grieve, their surviving child, Leslie Goosey, defends her brother.

Johnny couldn’t be a drug dealer, says Goosey, 24, and an artist and curator living in London. Though she acknowledges she and Johnny weren’t quite as close as they were as children, she recalls he was a quick study through public elementary schools, then Annunciation Orthodox School, then Lamar.

He graduated early, Goosey says.

“He didn’t like high school,” she says. “He thought it was too plain, too Mickey Mouse. He wanted more depth and independence in his studies.”

Johnny started college at the University of Houston, transferred to UT and graduated in December 2008.

Again, he finished ahead of schedule. But he lingered in Austin, waiting for Stacy to graduate and studying for his law school entrance exam.

Whether Johnny was smoking marijuana is irrelevant, Goosey says. “All I know is, a lot of people experiment with pot in college,” she says.

“But he definitely wasn’t doing drugs heavier than the usual college experimentation. He drove the family Prius. He was not a high-roller.”

And, she says, “He wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

Stacy finished UT on schedule in May. She and Johnny were planning to move back to Houston and their parents’ homes until she found a job and he settled on a law school.

Johnny seemed sure of his career choice, says attorney Kent Schaffer, who knew him as a playful little boy, then hired him to work in his law office the summer of ’07. By then, Johnny was 6-feet-2 with curly dark hair, big brown eyes and a fabulous smile.

“Everybody in the office was impressed with him,” Schaffer says. “He was very hardworking and always wanted to do more. He got off at 5:30, but he would stay until 7.”

Schaffer never had the chance to meet Stacy, but he says he knew of her because Johnny talked about her often.

Adds Leslie, “He was head over heels for Stacy. He was about to buy her a ring.”

The Goosey family hoped that she would say yes when Johnny proposed.

Troubling revelations

The Austin police held a press conference July 26, then filed court documents available to the public the next day — the same day the families would bury their children in a joint service.

The Barnetts and the Gooseys didn’t know it was possible to feel worse, but the police reports brought them to a new low.

The detective work, bolstered by interviews with six named witnesses and cell-phone records, showed that Johnny supplied Ricky Thompson with pot, which Ricky sold on the street.

But there was friction between the two young men, witnesses told police, because Ricky wasn’t paying Johnny for the dope. Ricky made excuses while his debts to Johnny mounted. Finally, witnesses claim, Ricky owed as much as $8,500, and Johnny grew impatient.

Records show Johnny called Ricky 19 times in the days leading up to the murder. The calls went unanswered. Finally, Ricky called Johnny on Monday, July 20, and again early the next morning. He agreed he would meet Johnny at 904 W. 21st.

That was Stacy’s second-floor apartment. Bill and Joyce Barnett thought it was safe and well suited to her needs because it was just a short walk to school. They also thought Stacy lived there alone.

Police think Johnny lived there, too. Based on witness accounts, they also say that Johnny, Stacy and assorted friends went to dinner the night of the 20th. At least one young man at the table told police that Johnny talked about “a kid” who owed him $8,500 for marijuana he had “fronted” him.

That night, police say, the young man from dinner slept over at the apartment. He left at 9:50 a.m., just as Ricky was climbing the stairs to the second floor. They passed each other on the stairs.

Ricky, who had been dropped off in the neighborhood by a roommate, was carrying a green duffel bag. He also had a .22-caliber pistol that police determined he borrowed from a friend.

At 10:12 a.m., Ricky called the roommate to pick him up. During those 22 minutes, police allege, Ricky shot Johnny multiple times in the head and went to the upstairs bedroom and shot Stacy twice, also in the head. Then he smashed their cell phones, picked up the bullet casings and left.

Two days later, while watching a TV news report on the murders, Ricky told another friend that he had killed Johnny and Stacy. He had to do it, he said, to avoid being robbed.

Early that Saturday morning, Austin police surrounded Ricky’s house on Alexandria Drive, arrested him and took him to Travis County Jail.

Police say Ricky confessed to them as well, saying he had to kill Johnny or Johnny was going to rob him.

If Ricky is indicted and convicted of capital murder, he faces a life sentence or the death penalty.

For now, he’s being held without bail.

Ricky’s attorney, Perry Minton, has little comment. His friends and family aren’t talking right now, either.

Ricky dropped out of Lake Travis High School when he was a senior. He’d been in trouble in recent years for smoking marijuana and stealing liquor from a Lakeway country club.

He owned a pit bull puppy. He drove an old BMW. He lived in a rented house in south Austin with several other young men. Neighbors saw lots of parked cars.

Earlier this year he earned the rank of Eagle Scout.

His membership in the Boy Scouts, however, has since been revoked.

Unanswered questions

Does the police account make sense?

According to Leslie Goosey, no. She says the police work has been poor and she and her family can’t understand why officers are smearing Johnny’s good name.

Both families wonder why, if the drug story is true, Ricky wasn’t running from Johnny? Besides, they ask, why listen to Ricky at all? If he confessed to a double homicide, what credibility does he have?

Leslie Goosey thinks Ricky wanted to rob Stacy and Johnny, and in fact, an expensive watch Dr. Goosey gave his son is missing.

Leslie Goosey also thinks the police and the university may be working in cahoots to find a fast solution to the case to avoid scaring UT students and parents.

That, says the mild-mannered Sgt. Reveles, finally provoked to respond, is just not true. The university has not contacted the police department about the case. Besides, he adds, Johnny and Stacy weren’t UT students, they were UT grads.

“We stand behind the report,” Reveles says. As for the watch, he adds without elaborating, “We don’t have any information that leads us to believe the watch was stolen during the course of the murder.”

At least two experts in Houston do find some twisted logic in the case.

One is Clete Snell, a criminal-justice professor at the University of Houston-Downtown.

When drugs are involved, Snell says, violent behavior is to be expected, and it is not going to make sense.

“What makes this case unusual,” he says, “is the status of the people involved.

“Everyone is asking why a kid who seemed to have a bright future would get involved in this sort of thing. For a lot of middle-class or upper-middle-class kids, it’s thrill-seeking behavior. The thrill of doing something illegal and high risk is attractive to a lot of people.”

Also, Snell says, some young people mistakenly believe that selling drugs is an easy way to make money.

“Clearly,” he adds, “a young man who gave away so much money in merchandise wasn’t very sophisticated.”

It’s possible Ricky really did feel threatened by Johnny, Snell says.

“In the drug culture, if somebody owes you money, eventually you’re going to go and get it,” he says. “You can’t go to a collection agency.”

Psychiatrist Bruce Perry says he is not at all surprised to hear of a wealthy young man selling drugs. He remembers a dope dealer in his medical-school class.

“Whether parents want to believe it or not, most successful dealers are upper-middle-class kids who make a connection with someone in a different strata of life,” says Perry.

But drug-dealing can be a phase, he adds, a short chapter in a long life.

“Parents would rather not hear about some of the real stuff that happens to kids at that age,” he says. “Usually they go on to become reasonable people.”

Some good news

The Barnetts have made the rounds of therapists, psychiatrists and priests, and so far no one has been able to explain why their daughter was killed.

“Only one guy knows,” Bill Barnett says, “and I wouldn’t trust him to tell me his name.”

During the day, Barnett tries to work and function normally. “But in my mind and spirit and soul,” he says, “I’m trying to find someone in a different world. Every day I have to get by, but what really matters to me is connecting to Stacy.”

Nights are worse. Before he drifts off to sleep, he imagines Stacy’s last few minutes of life. When he wakes up, he has to face the reality that she is gone.

Of course, the Barnetts are grieving for Johnny, too. Bill Barnett says he always liked Johnny, and that he and Joyce and the Gooseys hope to present a united front to the curious public. He acknowledges, however, that’s been harder of late. One comment Stacy made early in the summer haunts him.

Barnett says Johnny was signed up to take the law school entrance exam in June, then decided to put it off for another day. He’d already taken a course to help him with the test, and he’d invested in several books designed to help, too.

Barnett thought Johnny was under a lot of pressure to live up to high expectations.

The older man sympathized.

That’s when Stacy made the statement Barnett wishes he had pursued: “You know, Dad, Johnny has to get his act together.”

If he couldn’t or wouldn’t, she said, they might break up.

Today, Barnett finds some small comfort knowing that friends of Stacy and Johnny view the tragedy as a cautionary tale. Many of them have approached him and promised to live better, cleaner, more selfless lives and remember Stacy as an inspiration.

Barnett plans to do that himself. He tells the kids, “I don’t want our loss to perpetuate violence or hatred or guilt.”

If humanly possible, he wants something good, something positive, to come from the well of darkness.

He has a word for parents, too.

“Life is short,” he says, “sometimes much shorter than you think.”